Starting a PCA

PCA (Patient Controlled Analgesia)

Setting up a PCA (Patient Controlled Analgesia)

PCA is a very flexible form of providing analgesia for patients with no reliable enteral absorption, as long as:

-

the patient has a patent venflon

-

the patient is not confused and is able to understand the concept

-

the patient is physically able to press the bolus button

-

the ward nurses are trained in the management of a patient with a PCA

-

the patient agrees to stay in the clinical area

If the patient is already in moderate to severe pain, they may need a intravenous morphine or oxycodone titration before the PCA is started.

How to set it up:

1. Morphine is the 1st choice for patient controlled analgesia in the OUH.

Oxycodone may be used as 2nd line if there is a contraindication to morphine. *Oxycodone is 1.5 to 2 times stronger than morphine*

Rarely, fentanyl can be used but only in critical care units or the renal or transplant wards at the Churchill, nowhere else.

2. There is a PCA powerplan on ePMA (e-Prescribing and Medicines Administration).

3. The PCA syringe is prepared as 50mg morphine into 50mls of normal saline – giving 1mg/ml. The morphine solution comes pre-prepared in a bottle.

For consistently and simplicity, an oxycodone PCA is prepared in the same way: 50mg oxycodone in 50mls normal saline, giving 1mg/ml.

4. Prescribe the bolus dose that the patient will receive when they press the button – usually a 1mg bolus. Elderly patients may need a smaller bolus of 0.5mg.

5. The lockout time is 5 minutes and must not be changed. The lockout is designed so that the patient cannot overdose on the opioid as, during the lockout period, even if they press the button, they will not receive a dose.

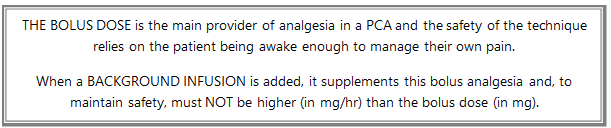

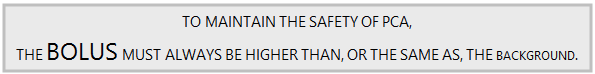

6. A background infusion is not usually needed but can be used if the patient is having severe pain despite good use of the bolus. Caution though: adding a background infusion increases the risk of opioid-induced ventilatory insufficiency.

7. As the patient’s pain changes, the PCA may need to be altered to match it.

Post-operative pain improves with time, so an initial high post-op programme will need to be reduced as time progresses. Equally, patients who are bed-bound for the first few post-operative days may have more pain later as they mobilise. These patients may need the PCA programme increased (see below) to enable physiotherapy and mobilisation.

8. The PCA should be stopped, and analgesia converted to oral medication, once the patient is able to eat and drink.

A typical set up for a PCA for an adult weighing more than 50kg is:

50mg of morphine in 50mls of 0.9% saline (as prefilled mix) with a 1mg bolus, 5 minute lockout and no background.

Naloxone should be co-prescribed with a PCA. Continue opioid-sparing analgesia such as intravenous paracetamol and, if appropriate, an NSAID.

The patient must be monitored according to the OUH PCA policy, with blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, sedation and nausea recorded.

Assessing if PCA is working:

1) Does the patient have significant constant pain? Assessing pain at rest.

If the patient has used fewer than 6 boluses per hour, encourage them to use their bolus more frequently to take control of their pain.

If they still have constant pain despite optimizing their bolus, then consider adding a background. Start a background infusion at 0.5mg/h in addition to the bolus.

A background infusion increases the risk of sedation and respiratory depression so close monitoring is essential.

A background must not be added if the patient is not already optimizing the bolus.

2) Does the bolus provide adequate pain relief? Assessing pain on movement.

If not, consider increasing the bolus, e.g. by 1mg, if the patient feels that the bolus is insufficient.

Examples of PCA Programmes- Bolus Only

![]()

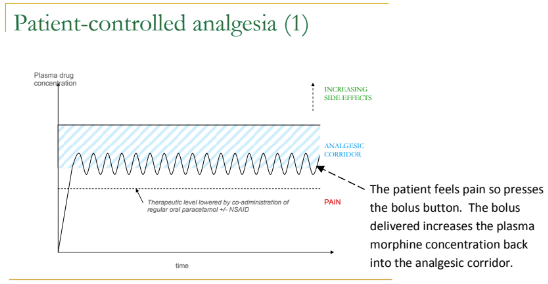

Before attaching the PCA, the patient may need an intravenous morphine titration [IV Morphine Rescue] to achieve sufficient morphine plasma levels to reach the analgesic corridor.

With a bolus-only PCA, the patient can regulate their own opioid consumption as below:

If regular Paracetamol and NSAIDs (unless contraindicated) are prescribed, the opioid requirement reduces by around 30%, which makes the PCA safer and reduces the incidence of opioid-related side effects (e.g. constipation, nausea and vomiting, confusion):

Pain at night and adding a Background Infusion

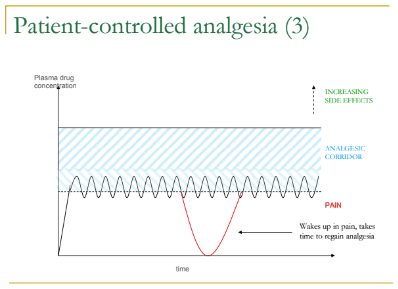

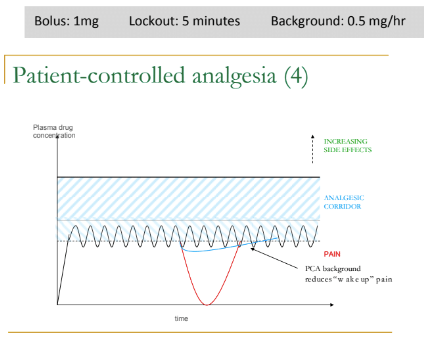

Occasionally, a patient may be comfortable during the day when they are awake enough to press the bolus button, but describe pain at night or severe pain on waking.

Adding a background infusion

A background infusion reduces the safety of PCA and increases the risk of sedation and respiratory depression. A background should only be added if the patient is optimising the bolus facility by using more than 6 boluses per hour. The background must be less than or equal to the bolus, but never higher than the bolus. A background can be useful for patients who describe constant pain at rest despite optimising their bolus:

![]()

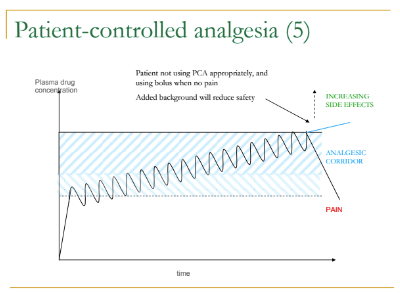

The need for caution when using background infusion:

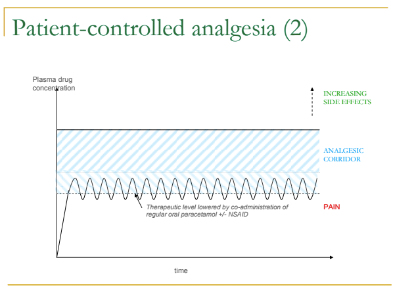

If a patient has bolus-only PCA and does not wait for pain but pushes the bolus button every 5 minutes, their plasma concentration of opioid will rise until they reach the upper limit of their analgesic corridor.

They will then become sedated, fall asleep and stop pushing the bolus button, allowing the plasma levels to drop back to safe levels (the black line on the diagram below).

However, if a background had been added to this patient's PCA, the plasma level will continue to climb after the patient has become sedated, thus increasing the risk of respiratory depression (the blue line on the diagram below):

Respiratory rate and sedation score must be closely monitored in these patients.

Patients with chronic pain who are already established on opioid analgesia and who now require a PCA for an acute exacerbation of their pain or for unrelated acute pain will require higher PCA doses [ PCA for Opioid Tolerant Patients]